“Katzenbach always surprises and never disappoints . . . he has a place on many ‘must-read author’ lists.”

-Bookreporter

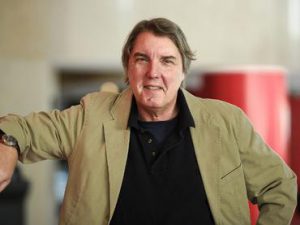

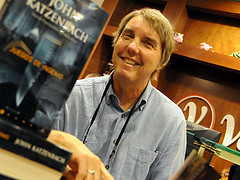

Bio

John Katzenbach’s career as a novelist began in 1982, with the publication of In The Heat of the Summer, an edgy crime novel that examined the cult of celebrity, fame and media ethics. A Book of the Month Club selection, this novel showed the newspaper industry at its height, and at the beginnings of its slide — and elected many of his experiences as a crime and courthouse reporter for both the Miami Herald and the now defunct Miami News. This novel was filmed as The Mean Season with Kurt Russell and Mariel Hemingway.

Since the publication of that first novel, John Katzenbach has written 12 other psychological thrillers and one acclaimed non-fiction book. Published in dozens of languages throughout the world, his novels have been on bestseller lists from Bonn to Buenos Aires. He has received awards in France, Germany and the United States. Three of his other novels have been filmed: Just Cause with Sean Connery and Laurence Fishburne in 1995; Hart’s War with Colin Farrell and Bruce Willis in 2002; and a French version of The Wrong Man — shown on France 2 Television as Faux Coupable. Two other novels — the international bestseller The Analyst and the award-winning bestseller The Madman’s Tale are currently in development with shooting dates in 2015.

His latest book — The Dead Student— is scheduled for publication by Grove/Atlantic/Mysterious Press in the fall of 2015, and simultaneously by Head of Zeus Publishing in Great Britain.

First thing to know: He hates middle age.

First thing to know: He hates middle age.

Actually, didn’t care all that much for being young either, where he was the in-between type of child that didn’t get listened to very much. Teenage was filled with existential readings and prep school angst, unrequited love and unrealized lust. That part was fairly normal. He had a reputation (deserved) as something of a long haired rebel and he takes considerable pride in having established new standards for academic and disciplinary restrictions and probation during his years at The Phillips Exeter Academy. Takes even greater credit for helping to create the school’s 9th Rule. That is, when he arrived at that cold, ivy-covered and unfriendly place in the 1960s, there were eight existing rules that could get you kicked out. He, along with two others (one who became a nationally-renowned internist and another a well-known and popular teacher) got busted by school authorities engaging in a practice that was clearly a violation of something – although, at that time, there wasn’t a clear-cut and well-defined rule against it. Suffice it to say it had something to do with significantly altered mental states. So, without the necessary rule to give school officials the sort of petty quasi-legal support they needed – they couldn’t kick him and his friends out. This might have been his first lesson in unintended irony.

Graduated just barely and went to Bard College, where he learned everything a young writer needs to know from incredible teachers – like Robert Rockman, Peter Sourian, Justus Rosenberg and the late Elisabeth Stambler and Mary Lee Settle — and wildly creative classmates. A wonderful place in the late 60s, filled with unbridled energy and fervent revolution. It remains so today, although probably less emphasis is placed on the revolution part. Had the opportunity while at Bard to occasionally yell at the two guys down the hall to turn their music down, which they usually did, being fundamentally nice fellows. They went on to some success as the rock group Steely Dan.

Followed college with an aborted trip to Iowa to inspect the creative writing program, where he realized that he didn’t have anything to write about except being young and wanting to write, which didn’t seem like particularly compelling subject matter. This translated into taking a job on the night city desk of the Trenton Times in Trenton, New Jersey (at the princely salary of $110 @ week). Trenton is famous for many things, not the least of which is a railroad sign above the Delaware River bridge, which states: Trenton Makes, the World Takes. One of Trenton’s main industries at the time was manufacturing condoms. There had to be some connection. Anyway, he stayed at the Trenton paper for three years, covering everything from town meetings concerned with leash laws to bloody prison riots, mental hospitals to murders until an unfortunate falling out with an editor resulted in him being summarily fired. At the time and despite numerous Page One stories, the editor informed him: “The only thing you are capable of writing is the weather ear….” That’s the little forecast that adorns the upper right hand corner on the front page – Cloudy Today, Sunny Tomorrow. He thinks he has successfully proven that particular editor to be mistaken.

Followed college with an aborted trip to Iowa to inspect the creative writing program, where he realized that he didn’t have anything to write about except being young and wanting to write, which didn’t seem like particularly compelling subject matter. This translated into taking a job on the night city desk of the Trenton Times in Trenton, New Jersey (at the princely salary of $110 @ week). Trenton is famous for many things, not the least of which is a railroad sign above the Delaware River bridge, which states: Trenton Makes, the World Takes. One of Trenton’s main industries at the time was manufacturing condoms. There had to be some connection. Anyway, he stayed at the Trenton paper for three years, covering everything from town meetings concerned with leash laws to bloody prison riots, mental hospitals to murders until an unfortunate falling out with an editor resulted in him being summarily fired. At the time and despite numerous Page One stories, the editor informed him: “The only thing you are capable of writing is the weather ear….” That’s the little forecast that adorns the upper right hand corner on the front page – Cloudy Today, Sunny Tomorrow. He thinks he has successfully proven that particular editor to be mistaken.

Anyway, went from there to the (late and lamented) Miami News, where he covered crime and punishment. Won some awards. Gained some notoriety for his reporting. Quit to write his first novel In The Heat of the Summer, which became a Book-of-the-Month Club selection, a bestseller published in nearly 20 countries and the movie The Mean Season. Returned to the Miami Herald, where he also covered crime and punishment with similar distinction. It was, parenthetically, a wonderful time to be a reporter in Miami. Everything that could go wrong did. Everything that could be bizarre was. And everything that might be outrageous, well, outraged.

Followed up his novel with his only non-fiction book, First Born – a Literary Guild selection. After that, he devoted himself to fiction. Two of his other books have been filmed – Just Cause and Hart’s War. Three others are currently in “development” which means that if all the chips fall properly, they will some day land on the big screen. Finally left newspapers in 1987 after publishing the New York Times bestseller The Traveler – a favorite of thriller buffs worldwide and the occasional serial killer. Although no longer a reporter, he still longs for the wonderful sensation of excitement that accompanies pursuing a big story. Now lives in humdrum Western Massachusetts, an incredibly reasonable place except in the winter (which sometimes seems like half the year). Published all over the world, received many awards. Married to the writer/journalist/professor Madeleine Blais, whom he met in Trenton. Two children neither of who wants to work in anything other than the Arts, despite his oft-spoken pleas to the contrary (which mask his real delight. Does the world really need another lawyer or investment banker? He wonders.) One dog: a standard poodle that seems to only enjoy barking and eating and sleeping, with an emphasis on the latter two. He used to be an avid runner, but now merely lurches and staggers a daily five miles. His only real hobby is fly fishing, which he considers himself to be fairly adept at —which means he occasionally encounters a fish stupid enough to be tricked by some feathers.

And, if you really want to know why he hates middle age it is this: When you are young, the adventures you have, that inform the words you write and the words you will write, are real and palpable. As you get older, they become farther apart – and one must rely increasingly on their imagination and their memory of things observed in the past. Nothing actually wrong with that of course: It’s just not nearly as much fun.

On Dogs and Years, not Dog-years.

On Dogs and Years, not Dog-years.

Now that I am getting a lot closer to the “end” of middle age, I should temper my criticisms of that time of life. It’s not so bad, considering the alternatives. Hate now seems a truly foolish choice of words. Tolerate might be better, especially when envy looms on the aging horizon. In an odd way, it seems to me that the best way to get older is to work harder at recovering those qualities that made being young work so wondrously. This simple observation, I suspect, is one that comes as revelation to some, and is a cliché and a truism to others. Sigh.

If this were a Hollywood movie, we would have to add in some thunderous orchestral blast to accompany these thoughts in order to give them sufficient gravitas and underscore the drama.

Now there’s an idea: for so much of our lives, we duck and avoid intensity, relying on routine and preferring what we imagine is normalcy. But, in truth the moments that become most memorable are those where the stakes are heightened. This is just as true for a novel as it is for day-to-day life. The older I get, the more I think the bard was absolutely right: all the world is a stage, and we are all players on it.

Of course, disagreeing with Shakespeare is probably an unwise course of behavior for any scribbler.